PharmSmart: Nausea and Vomiting

By AccentCareThis month we are going to be talking about the topic that may make us nauseous just thinking about - nausea and vomiting. Let’s get moving by first talking about some definitions that could be helpful in our journey. Nausea is generally the sensation felt right before vomiting, whereas vomiting is the forceful evacuation of gastric contents from stomach and out of the mouth. A less commonly used term is retching, which is the repetitive, active contraction of abdominal muscles, generating pressure to evacuate contents of stomach, and dry heaving is when no contents are expelled from the mouth.

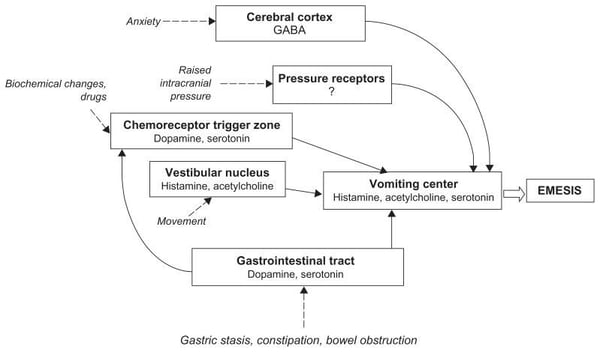

Now that we know our vocab, why does nausea and sometimes with or without, vomiting occur? There are many etiologies of nausea and vomiting. There are four different pathways causing nausea and vomiting:

- Stimulation from the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ)

- Gastrointestinal (GI) tract

- Vestibular region

- Through the cerebral cortex

Inputs from the GI tract and the vestibula send signals to the CTZ to stimulate the emetic complex, whereas the cerebral cortex bypasses the CTZ and directly stimulates the emetic complex. Each of the pathways are mediated by receptors leading to nausea and vomiting. Spoiler alert, predicting where the receptors are firing (and which neurotransmitters are stimulating them) and stimulating the emetic complex based on patient presentation is how we will choose medications to treat or prevent nausea and vomiting.

The receptors that are responsible for nausea and vomiting include but are not limited to dopamine, serotonin, histamine, acetylcholine, and GABA. Some of these receptors also have multiple subtypes producing various effects. Let’s start with the CTZ. The CTZ is stimulated by electrolyte abnormalities, renal and hepatic failure, sepsis and medications. Medications causing nausea and vomiting include, but is not limited to, chemotherapy, opioids, antibiotics, oral hypoglycemics. The receptors that work in the CTZ include dopamine (D2) and serotonin (5-HT3 and 5-HT4).

The GI tract is the next area responsible for causing nausea and vomiting that we will discuss. Here, triggers can result from anything that obstructs or slows the GI tract from routine operations. Common examples include constipation, obstruction, chemotherapy, radiation, gastritis, gastric ulceration, and the list goes on. Probably one of the more common and least kind adverse effect of chemotherapy is the associated nausea and vomiting, which is thanks to the interaction at the CTZ and in the GI tract. Vomiting soon after eating is a common symptom of a bowel obstruction. The receptors at play here include dopamine (D2) and serotonin (5-HT3 and 5-HT4), just like the CTZ. Common causes for vestibular stimulation are motion sickness, or a vestibular tumor or inflammation, such as vestibular neuritis. The most common neurotransmitter to blame is histamine (H1) and acetylcholine (ACh).

The final pathway we will discuss is in the cerebral cortex. Anxiety, increased intracranial pressure, unpleasant sights, smells, tastes and psychiatric disorders are common triggers within the cerebral cortex. The active neurotransmitters here include GABA and histamine (H1).

For my visual learners, here is a synopsis of what we just talked about:

If left untreated, nausea and vomiting can have a significant impact on quality of life for patients. Dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, anorexia, weight loss, and emotional distress are just a few consequences patients may experience with chronic nausea and vomiting (occurring for longer than one month). Luckily, we have many tools in our pharmacologic toolkit to help us treat or prevent nausea and vomiting. And if you were so bold as to read the spoiler earlier, you have an upper hand on how we tackle treatment.

So let’s talk treatment!

We are going to start with the antidopaminergic medications. As the name suggests, they block the dopamine receptors in the GI tract and CTZ. Some antidopaminergic agents also display prokinetic effects, acting in the GI tract. Our common therapies in this class are metoclopramide (Reglan, which is our prokinetic agent, and also interacts with serotonin receptor), prochlorperazine (Compazine), promethazine (Phenergan) and haloperidol (Haldol). Since haloperidol is an antipsychotic, we could see some extra-pyramidal effects. Other adverse effects seen in the class include sedation and hypotension. Importantly with using this class, we want to rule out bowel obstruction. Additionally, we want to keep away from these therapies in patients who have movement disorders, as the antidopaminergic agents can exacerbate these disorders. All of these therapies are available as a tablet, oral solution, and parenteral formulations.

Next up are the serotonin antagonists. Similarly, the serotonin antagonists block the serotonin receptors in the GI tract and CTZ. Most commonly used is ondansetron (Zofran). Due to price reasons, less commonly used and available are granisetron (Sancuso), dolasetron (Anzamet) , and palonestron (Aloxi). Most common adverse effects include constipation and headaches. Less of a consideration in the hospice and palliative care patient population is the risk of QTc prolongation (since we don’t routinely obtain EKGs), increasing the risk for a potentially fatal arrhythmia known as torsades de pointes. This class is commonly used in the treatment, and sometimes prevention of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. These agents are available as oral tablets, oral disintegrating tablets (ODT), and parenteral formulations.

Antihistamine agents can also be used as a treatment. They would target the histamine receptor acting in the vestibular region of the ear and the cerebral cortex within the brain. Common players here include hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine, and meclizine. As we know with anticholinergic agents, common side effects include “can’t see, can’t pee, can’t spit, can’t… have a bowel movement” - exacerbate glaucoma/blurry vision, urinary retention, dry mouth, constipation, additionally sedation and orthostatic hypotension. These agents are available as oral tablets and solution. Less commonly, antihistaminic agents may cause or worsen delirium, an extension of the anticholinergic effects of antihistamines.

The anticholinergic agent that we see most commonly used is scopolamine (Transderm Scop). It targets the acetylcholine receptor in the vestibular region, particularly useful for motion sickness induced nausea. Scopolamine is conveniently available as a transdermal patch, which is administered behind the ear and kept on for 72 hours. However, the most common adverse effects include drowsiness and dry mouth.

We also have the GABA agonists, including the anxiolytics. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter so by increasing the GABA concentration, hopefully nausea and vomiting will decrease. Our most common anxiolytics used include alprazolam and lorazepam. Anxiolytics have weaker evidence for support in the treatment of nausea, due to the adverse effects seen especially in older adults. However, anxiolytics have been used for anticipatory nausea and vomiting, especially associated with chemotherapy.

Another class used for nausea and vomiting include the cannabinoids. The mechanism of the cannabinoids is less understood for nausea and vomiting. The available prescription medication approved for nausea and vomiting is dronabinol, which comes as an oral tablet. Adverse effects include drowsiness, sedation, hypotension, and euphoria.

The final class of medications we will cover are corticosteroids. The mechanism of alleviating nausea and vomiting is unknown, but it has been shown to be beneficial in cancer associated nausea and vomiting, reducing inflammation, pressure on GI tract, and reducing intracranial pressure. Most commonly used is prednisone, methylprednisolone, and dexamethasone. These agents are available as oral tablets, solution and intravenous formulations. Common adverse effects seen with acute use of corticosteroids include hyperglycemia, hypertension, mood swings, insomnia, and fluid retention. Caution should be used in patients with uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure.

Now that you are a master in treating nausea and vomiting, let’s take these skills for a test drive.

Our patient YT is a 78 year old male who went through a 5 year battle with lung cancer and has just recently decided he is no longer interested in feeling so rotten after chemotherapy treatments, including nausea. Now that he is not hooked up to the infusion line for most days of the week, he is living his best life touring all of the national parks in the country. He comes to you on his way from Acadia National Park in Maine to discuss that he has been having awful nausea and actually vomited a couple of times on the road. He is quick to blame his wife’s driving. Which emetic pathway is likely causing YT’s nausea in the car? Which antiemetic are you most likely to recommend for his current complaint?

- CTZ, ondansetron and try traveling by plane instead

- Emetic center, metoclopramide and get out of the car

- Vestibular region, scopolamine and get out of the car

- GI tract, alprazolam and try traveling by boat instead

If you picked “C” you are ONE SMART COOKIE! Riding in the car can easily cause motion sickness, which is a vestibular effect. As we discussed, the management is an anticholinergic agent, such as transdermal scopolamine (and get out of the car!).

When a patient complains of nausea and/or vomiting, make sure you do a thorough assessment, as we do for pain and other symptoms:

- Precipitating – what brings the nausea on or makes it worse?

- Palliating – what relieves the nausea/vomiting (from a non-drug perspective)?

- Previous treatment or therapy – what have you tried (drug therapy), how well did it work and did you have any side effects?

- Quality – what words would you use to describe the nausea/vomiting

- Region/radiation – this is a tough one, but we all understand how nausea can be in your tummy, vs. that nauseated/dizzy feeling in your head

- Severity – how intense, or how distressing is the nausea/vomiting? You can use the 0-10 scale

- Temporal – how long have you had the nausea and vomiting? Is it persistent or does it come and go? If it comes and goes, how many episodes per day and how long does the episode last?

- Associated symptoms – obviously, asking if the primary complaint is nausea, or vomiting, or both? What symptoms accompany the nausea (dizziness, etc.). What does the nausea/vomiting keep the patient from doing? Sleeping? Eating? Has it affected the patient’s mood?

This information will help you determine the pathogenesis of the nausea/vomiting, pinpoint the most likely neurotransmitter, and then the best, targeted drug therapy. Now you’re an expert!

And now some questions for the road….check all that apply!

Which are the two most common neurotransmitters involved when the CTZ is triggered?A. Histamine

B. Serotonin

B. GI tract

C. Vestibular region

D. Cerebral cortex

Metoclopramide is useful as a prokinetic agent. What receptor does it work on?

A. Dopamine

Answers

- B, C

- D

- A, B

PharmSmart is a monthly article dedicated to best practices in drug management for patients nearing the end of life, with a little cheer and lightheartedness woven throughout. It is edited by Dr. Mary Lynn McPherson, PharmD. Dr. McPherson is the Executive Director of Advanced Post-Graduate Education in Palliative Care at University of Maryland. Dr. McPherson is a consultant pharmacist to Seasons, and answers complex medication questions for our clinical teams at all hours of the day or night. She is a nationally-recognized expert in medication management for hospice and palliative care patients.

This issue of PharmSmart was authored by Abby Stevens, PharmD

PGY2 Pain and Palliative Care Pharmacy Resident, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy